To Posterity

From the exhibition

We Are Living on a Star,

Henie Onstad Kunstsenter

In the summer of 1936 the Norwegian poet and dramatist Nordahl Grieg (1902–1943) was alone on an island off the southern coast of Norway. He had gone there to start work on a new theater piece, Nederlaget: et spill om Pariserkommunen (The Defeat: A Play about the Paris Commune). The theme was not incidental; at that time the first battles in the Spanish civil war were being fought between the republican army and General Franco’s fascist forces. Grieg, a communist who had been following the reactionary forces progress in Europe with grave concern, saw early on the parallels between Franco’s attack on Spain’s popularly elected government and the Versailles troops’ brutal suppression of the French workers’ revolution in 1871. In retrospect the play about the hopeless struggle of the idealistic Communards against a massive superior military power can be read as a bleak prophecy about the fate the International Brigades would suffer in Spain. The title, The Defeat, was strikingly precise.

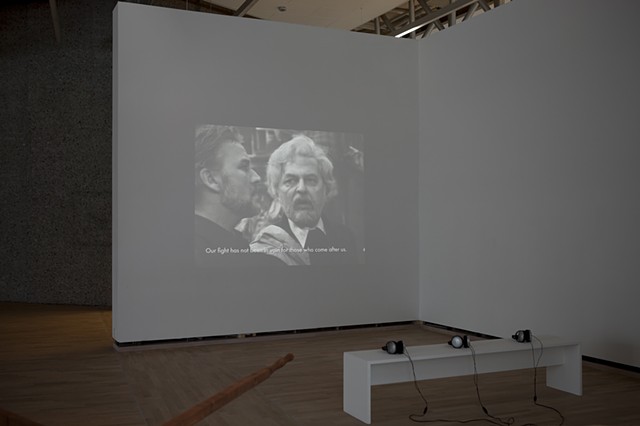

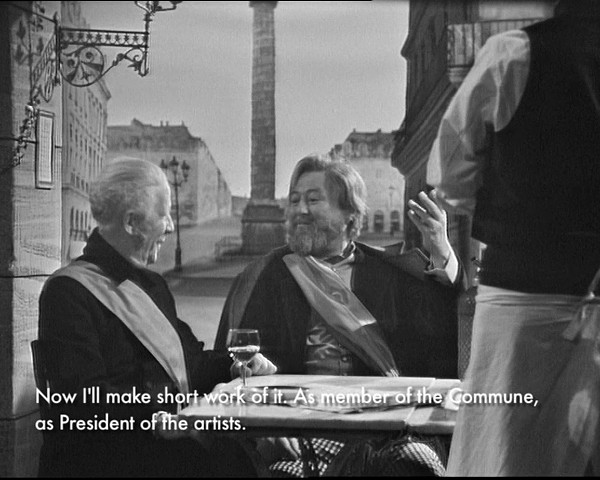

That same summer during which Grieg penned The Defeat, he also wrote the poem To the Youth. As in The Defeat, Grieg asks here whether it is possible to live by ideals of goodness and human decency in encounters with evil and violence. In Norway, the themes expressed in this poem had renewed relevance after July 22, 2011. To the Youth became an important unifying reference point in the nation’s collective grieving process after the terrorist attack. In To Posterity, Per-Oskar Leu utilizes excerpts from a Norwegian television production of The Defeat from 1966. He has chosen to take a closer look at Grieg’s depiction of the French painter Gustave Courbet, one of several characters in the play who are based on historical figures. A socialist, Courbet sided with the Communards during the revolution in 1871, and he is remembered specifically for having partaken in tearing down Napoleon’s war memorial at the Place Vendôme in Paris. In The Defeat the painter is portrayed as a flighty and thorough cliché of an artist, as is clearly apparent in the following exchange between the teacher Gabrielle Langevin and the young man Pierre:

PIERRE: We who are poor live like pigs. And those who have money also live like pigs. It all comes down to the same thing.

GABRIELLE: Don’t you believe there is such a thing as progress in the world?

PIERRE: Oh, sure. Just look at those two over there. [Points over toward Courbet and Rigault.] They sit in the café there every day and talk about injustice. If they got into power, they would sit at a more elegant café. I damn well do believe in progress.

In the characterization of Courbet one can sense the contours of a central conflict in Grieg’s own oeuvre; that is, the notion of correspondence between life and poetry, between belief and action. For Grieg, who viewed form and content as of equivalent value in his literary work, faith in art’s usefulness as a political tool was a personal matter. In a dialogue between the revolutionary agitator Louis Charles Delescluze and Courbet toward the end of The Defeat, Grieg is merciless in his criticism of the French painter’s indefinite position:

DELESCLUZE: My friend, I am afraid that no one can help you. Your name stands at the top of the list of those whom the officers hate, because you tore down the Vendôme column.

COURBET: I didn’t want to tear it down. “Screw it off,” I said. I meant, move it to another place. Besides, I shall take my full responsibility to posterity.

DELESCLUZE: Understand that you must take it now.

COURBET: Take responsibility for what? For blood and fire and corpses? I had a dream of justice, and you people have carried it out stupidly. Look at this picture of Paris today, and look at my own canvases, and then answer me: Is this picture by me, can I be responsible for it, can I sign it G. Courbet? Never, I say.

Around the film clips from The Defeat Leu has constructed a scenography consisting of sculptural elements. Two apparatuses, both made of wood, recreate the technology which at the time was used to erect, and thereafter topple, Napoleon’s controversial memorial. In Leu’s work the vertical hoist and the horizontal winch serve as images of an ideological tug-of-war with connections from the Paris Commune to our own era. In addition, Leu displays a collection of original prints from the 1870s that in various ways illustrate the Vendôme Column’s turbulent history.